“Sometimes I feel like a motherless child,

a long, long way from home.”

—Traditional

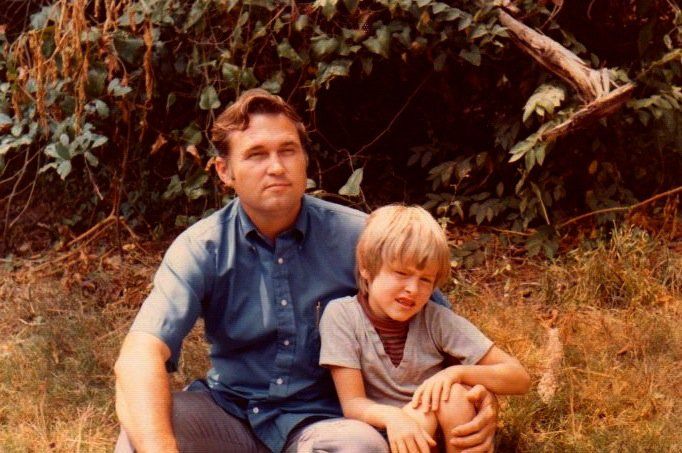

When I was a kid in Tennessee and Georgia I knew very little about my mother.

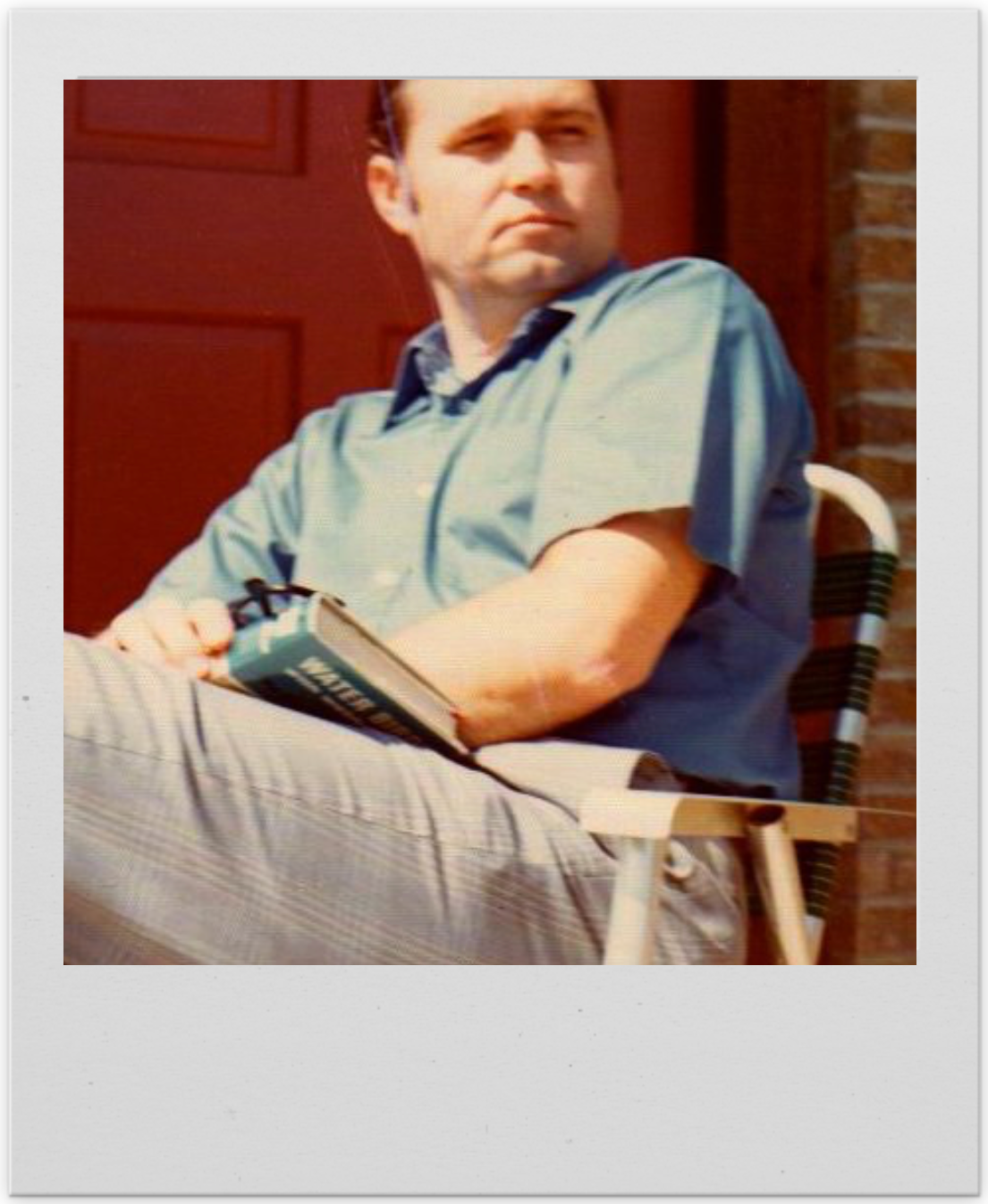

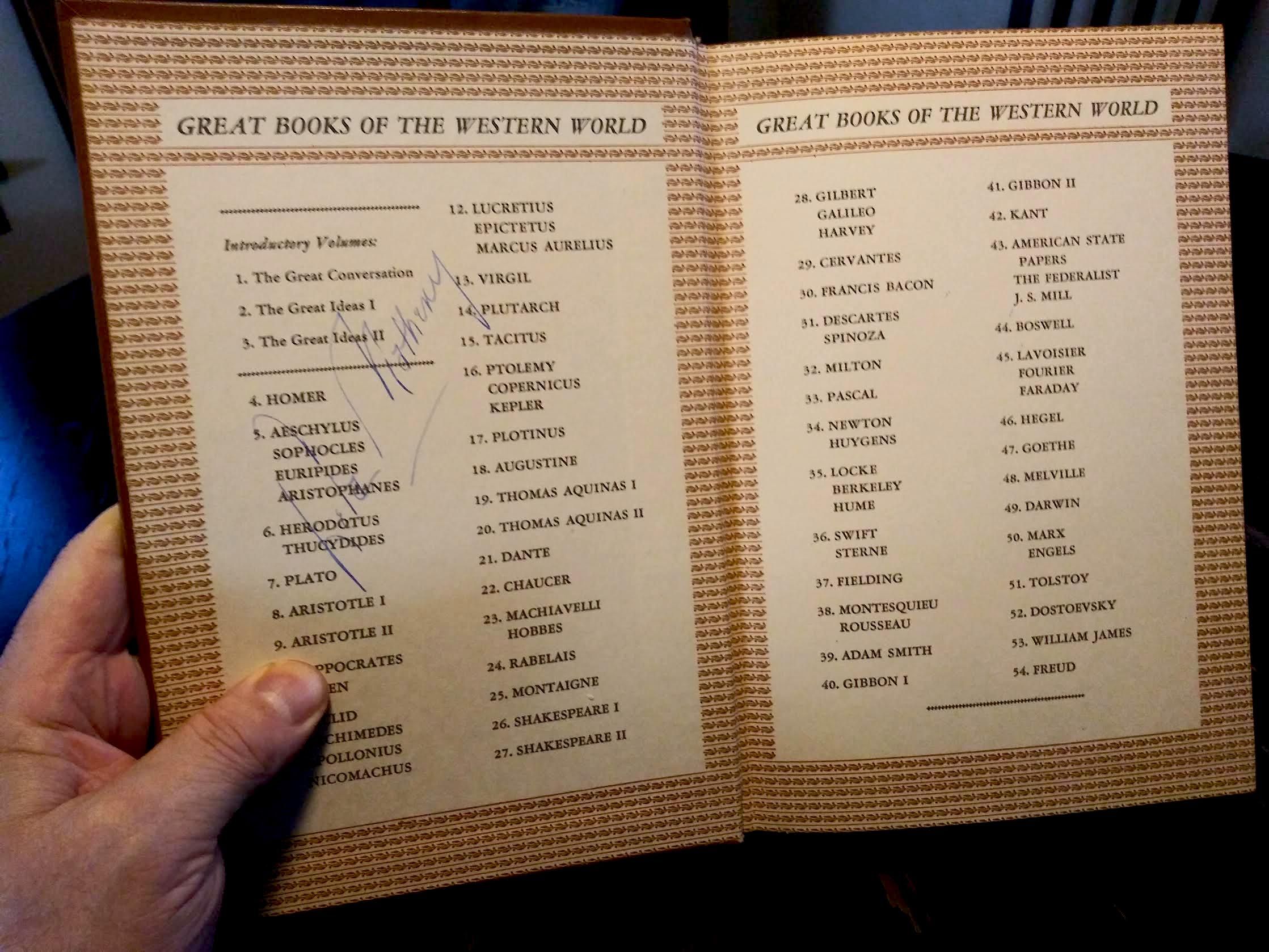

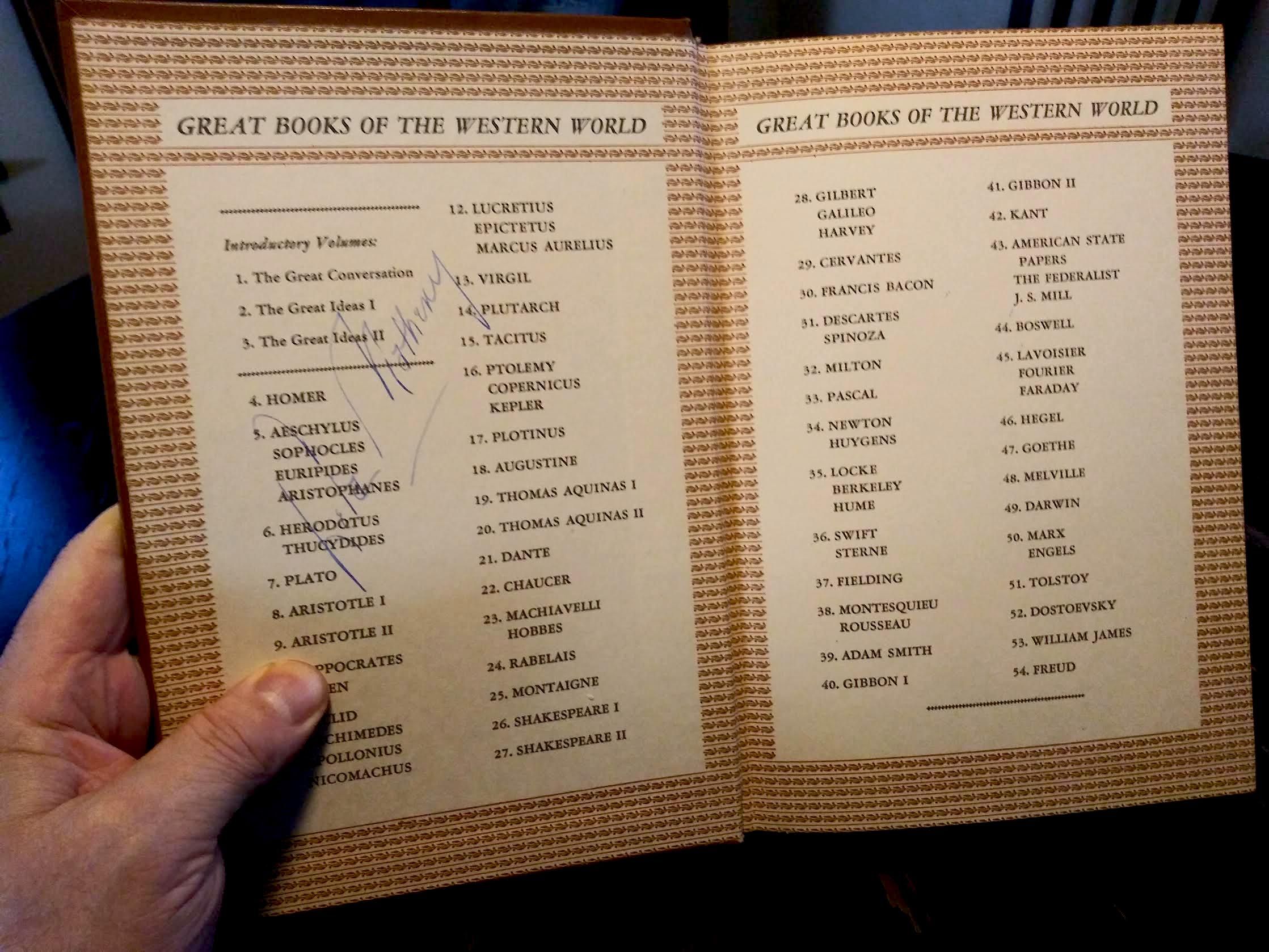

I knew her name. “Lela Matheny” was written in ballpoint pen on the inside cover of all our books. I knew she was a talented artist, too. We had several of her framed oil paintings hanging on our walls. And I knew she was movie-star beautiful. Although Dad was reluctant to speak of Lela, he did give me a single photo of her which I treasured and kept hidden away in a drawer.

“Lela Matheny” was written in ballpoint pen on the inside cover of all our books.

“Lela Matheny” was written in ballpoint pen on the inside cover of all our books.

The only other thing I knew about Lela was that she broke my father’s heart.

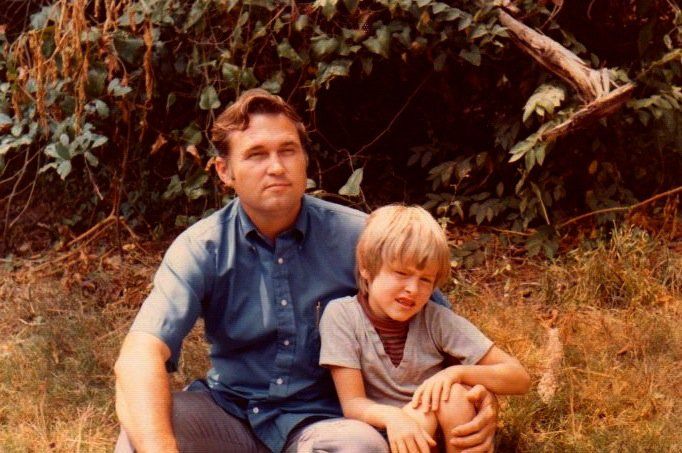

“Shortly after you were born,” Dad explained, “Lela ran off with her lover in the middle of the night. They took my car and went to Mexico. Lela got herself a Mexican divorce and a Mexican marriage to the other guy. As far as I know, they’re still together.” He would repeat this story many times over the years, always emphasizing the words “Mexican divorce” and “Mexican marriage” as if that particular detail somehow signified illegitimacy or proved how unjustly he’d been treated.

If I felt any sadness over losing Lela I certainly wasn’t aware of it. I didn’t remember her, so how could I miss her? I was a happy kid with a loving father and a revolving door of kind female caregivers. But I was understandably curious about the woman who gave birth to me. I wondered where she was, why she left, what her life was like now.

Whenever I asked my Dad these things, he would repeat his “Lela ran off” refrain, and would shut down any follow-up questions with “Aw, you don’t want to know about her! She’s crazy!”

I was understandably curious about the woman who gave birth to me.

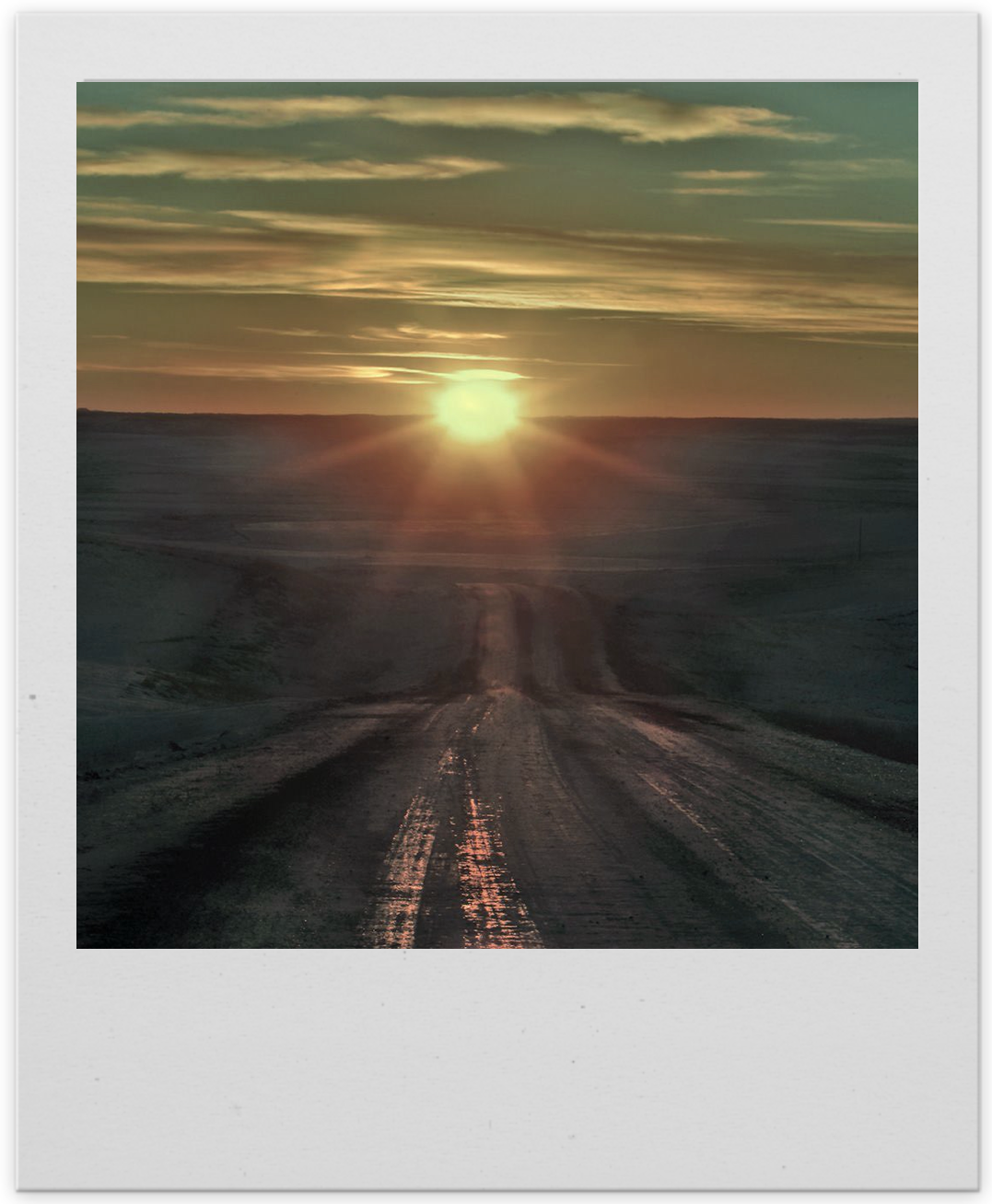

As far as I knew our only contact with Lela was the birthday card I received each year at Christmas. There were never any messages inside, just “Love, Lela” in the same familiar handwriting. There were never any return addresses on the envelopes, either, but I always noticed the postmarks. Each year the card would arrive from a different place: Key West, Seattle, New York, Santa Fe, Ann Arbor.

“Looks like Lela’s in Bozeman, Montana,” I said to Daddy Bill after my thirteenth birthday. “Why do you suppose she moves around so much?”

I expected his customary evasiveness, but this time the old man surprised me. “Son, you’re old enough to know that your mother’s husband is a federal criminal,” Dad said soberly. “They have to keep moving because they’re on the lam. Tom is wanted by the feds.”

“No kidding?” I asked. “What did he do?”

“Mail order fraud,” Dad replied. “He sells fake chinchilla furs or somesuch.”

I had no clue what a chinchilla was, but the notion that half my DNA might come from a mysterious, beautiful, crazy, vagabond artist/criminal? The idea intrigued me. I needed to meet this person.

"He sells fake chinchilla furs or somesuch."

"He sells fake chinchilla furs or somesuch."

It’s the summer of 1979 in Tucson, Arizona, and I’m living it up in our new Catalina Foothills apartment. Dad is teaching summer school so I have my run of the place. I get to sleep late and have friends over. We do whatever we want, when we want, free from adult supervision.

Our activities are fairly harmless: we crank up the air conditioner, make giant Dagwood sandwiches, drink gallons of sun tea, and watch creature features on the tube. We listen to records in the Den of Iniquity. Sometimes we ride our bikes down to the Circle K for Mad magazines and microwave burritos, or head over to the Coronado clubhouse to play air hockey and gawk at the high school girls sunning themselves by the pool.

Any self-esteem I lost at Marana has been fully replenished. I now have friends, freedom and, thanks to my paperboy job, plenty of spending money. As if I needed any additional ego boost, they’ve been saying my name on the radio lately (“trumpet solo by Dmitri Matheny”) because I’m playing the mariachi classic “La Paloma” in the Fiesta de los Niños at El Con Mall. I feel special again for the first time since we left Brookstone.

I’m playing the mariachi classic “La Paloma” in the Fiesta de los Niños at El Con Mall.

It’s mid-morning when the phone rings in our dark apartment. I shuffle into the kitchen and wipe the sleep from my eyes as I lift the receiver. What have I won this time?

“Dmitri?” says an unfamiliar female voice. “This is Lela.”

“Lela like my mother Lela?” I ask.

“That’s me,” she says. “How are you?”

“Surprised,” I reply.

“Listen, I’m in Tucson,” she says. “I live here. What are you up to today?”

“Nothin’ much,” I reply, bewildered.

“Would you like to go with me to the art museum?”

Half an hour later I answer the door and there she is, the pretty lady from the photo, looking not unlike Suzanne Pleshette in her high-collared lime green pantsuit, white silk scarf, and oversized sunglasses. I lock up the apartment, follow to her car, and slide into the passenger seat next to her. I can’t believe she’s really here.

Unlike my taciturn father, Lela turns out to be an absolute chatterbox. She talks nonstop as we walk through the museum galleries, jumping randomly from one non sequitur to the next, dramatically whispering then laughing loudly, dropping names I don’t know, passionately offering her opinion on every exhibit. The words tumble out of her but I barely comprehend their meaning. I’m too preoccupied with studying her every move and mannerism. Do I take after Lela? She strikes me as stylish and sophisticated, yet insecure and more than a little phony.

After the museum we walk across the street to a frozen yogurt shop called the Frosty Frog. Lela orders a mint chip froyo to match the vivid green of her outfit, then lights a long slender cigarette, all the while babbling like the giddy guest on a late night talk show. Something in her affect makes me feel diminished, as if I’m merely a spectator in the movie of her life. It’s only at this moment, looking across the table at her, that I’m finally able to accept the reality of this surreal afternoon.

So this is my mother.

Lela orders a mint chip froyo to match the vivid green of her outfit.

When Daddy Bill gets home from work he finds me sitting silently in the living room.

“How was your day, Bub?” he asks.

“Well Dad,” I reply, “I think you ought to sit down for this.”

In my memory the revelation that I’d spent the day with my bio-mom was a complete surprise to Daddy Bill. He didn’t mind that we'd met, but he seemed genuinely shocked to learn that Lela was in Tucson, and mystified by how she got our phone number. In hindsight I suspect he knew more than he let on. When it came to Lela, Dad played his cards very close to the vest.

I rode my bike over to Lela and Tom’s place several times that summer. Their condo was modest, even smaller than our apartment, but it was brand new, adjacent to a magnificent golf course, and furnished with midcentury modern Scandinavian decor that looked like something you’d see in the pages of a high-end design catalog.

Lela's husband Tom was an overly tan charmer with “trust me” eyes and a full head of gray-blond Banacek hair. He wore polo shirts and khakis, told silly jokes, brandished a fat bankroll, and flashed blindingly white teeth whenever he smiled, which was often. He spent most of his time either on the phone or on the links.

“What exactly does Tom do for a living?” I asked Lela, thinking of the chinchillas and whatnot.

“Oh, this and that,” Lela said with a dismissive wave of the hand. “Tom’s what’s known as an entrepreneur.”

It was the first time I’d ever heard the word. To this day when anyone uses it I think of Tom and his Cheshire Cat grin.

I expected Dad’s reunion with his ex-wife, and the man she left him for, to be awkward, but the three of them got along just fine. They reclined in their chaise lounges, swilling gin cocktails and playing “remember when” like old friends. Later when we all went to dinner together at La Fuente, the mood was entirely convivial, or so it seemed to me.

On one occasion Dad invited Tom over to play tennis while Lela stayed behind to give me a painting lesson. I still remember how she taught me to use complementary colors for the shadows, and the way she demonstrated the proper technique for washing a paint brush by making small soapy circles in the palm of my hand.

Dad invited Tom over to play tennis while Lela stayed behind to give me a painting lesson.

Dad invited Tom over to play tennis while Lela stayed behind to give me a painting lesson.

I tried to engage Lela in meaningful conversation but quickly learned that she had no interest in being real with me. Having grown up in the south I'm no stranger to tall tales, but Lela was a full-on fabulist. She seemed incapable of giving a straight answer.

A simple query like “do I have any brothers or sisters” prompted a hyperbolic description of her own brother, a strikingly handsome, independently wealthy, eccentric genius, more clairvoyant than Edgar Cayce, who lives in a mansion and invents rockets for a secret government agency. Ahem.

When asked about her childhood, Lela launched into a series of Bunyanesque tales about a magical, mythical Cherokee ancestor named “America” who married a Scotsman named “McGee” to become “America McGee.” Each story was more outlandish than the previous, but none shed any light on Lela’s actual life.

Lela delivered these far-fetched family fables with earnest enthusiasm, oblivious to how ridiculous they sounded. Eventually I stopped asking questions altogether and just surrendered myself to her whimsy.

We saw each other several times that summer but she never gave up any credible intel. Nor did she seem interested in learning anything about my life or thoughts or feelings. I learned what I could about Lela through observation alone.

In late summer Daddy Bill and I were sharing a bag of Fritos and watching 60 Minutes when he put his hand on my shoulder and said, “I’m glad you’ve enjoyed getting to know Lela and Tom, but you’d better prepare yourself, son. At some point they’ll disappear again, probably without warning. I don’t want you to get your feelings hurt.”

Dad was right. A few days later Tom’s name appeared in an Arizona Daily Star article about interstate commerce irregularities. I called the condo and, sure enough, the number was disconnected. I rode over on my bike and, no surprise, the place was empty.

It would be another 23 years before I would meet Lela again.

Lela in 1965 (L) when I was born, and in 2002 (R) when I met her the second time.

MEETING LELA

Part 1 — The Frosty Frog

Part 2 — Chattanooga

Part 3 — Adventureland

Part 4 — America McGee

Part 5 — Under The Stars

Part 6 — Gifts

Part 7 — Biscuits & Gravy

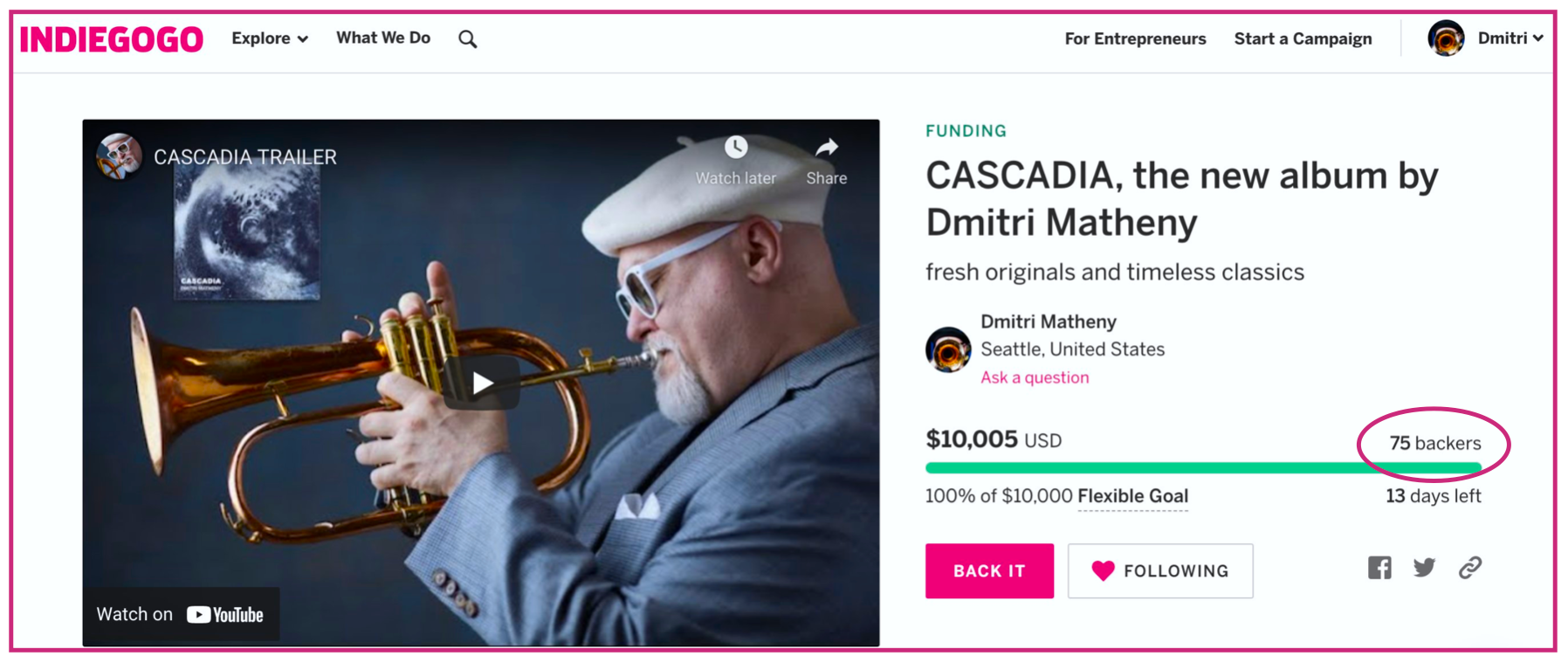

After coaching the Bloomfield Hills jazzers, I met up with my band for a 4-night run at one of our favorite venues: the historic Cliff Bell’s in Detroit! We made lots of new friends, and our pianist even got to play Stevie Wonder’s Rhodes! Among the extramusical highlights: walking in Palmer Park, visiting the Detroit Institute of Arts, and enjoying Mama Lisa’s home cooking. Excelsior!

After coaching the Bloomfield Hills jazzers, I met up with my band for a 4-night run at one of our favorite venues: the historic Cliff Bell’s in Detroit! We made lots of new friends, and our pianist even got to play Stevie Wonder’s Rhodes! Among the extramusical highlights: walking in Palmer Park, visiting the Detroit Institute of Arts, and enjoying Mama Lisa’s home cooking. Excelsior! Made it to the mitten to find the fall colors in full effect! First order of business: a Steak & Shake burger!

Made it to the mitten to find the fall colors in full effect! First order of business: a Steak & Shake burger!

published 50 memoir blog posts

published 50 memoir blog posts

played 5 live stream shows

played 5 live stream shows

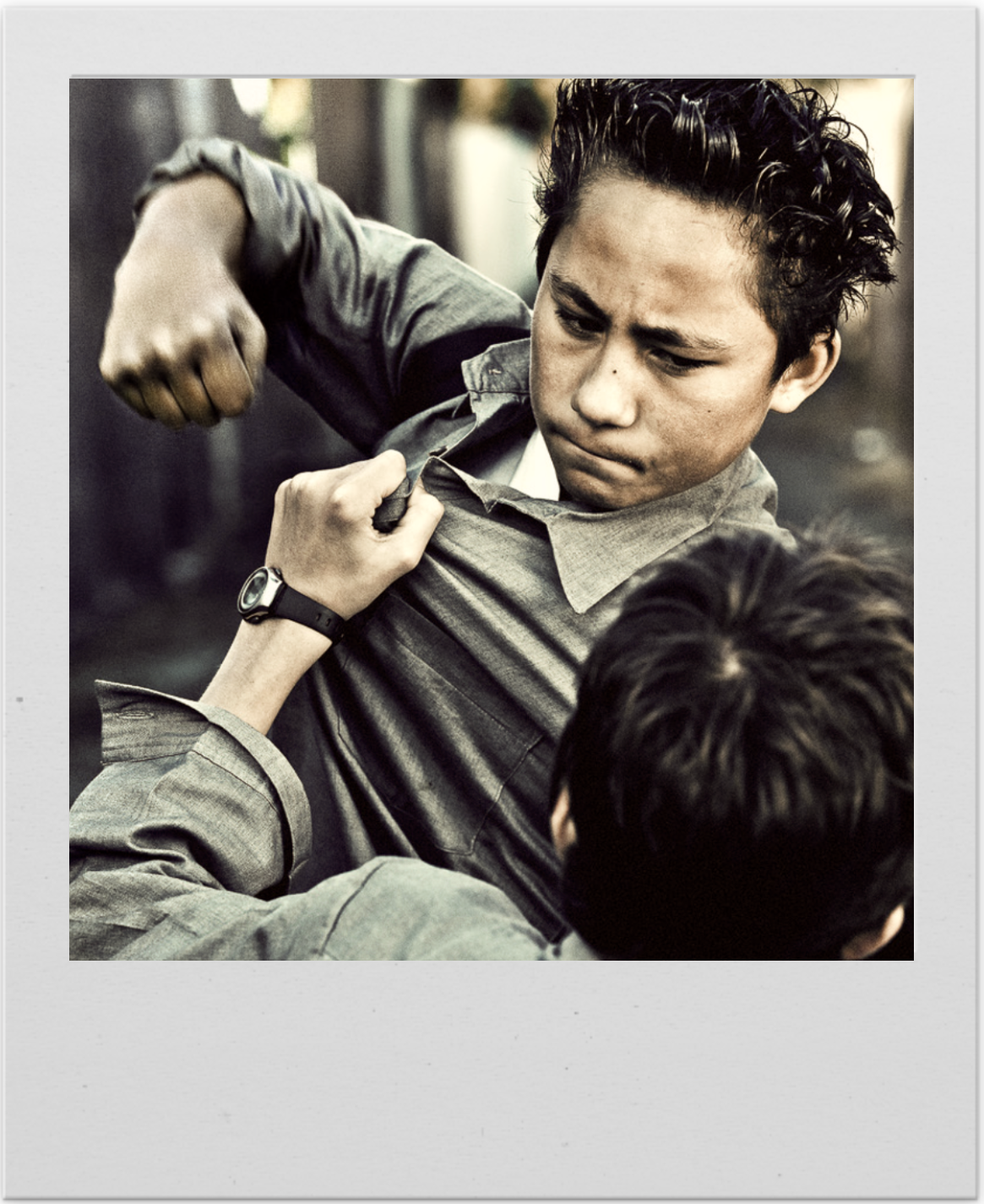

There are fist fights every single day at Marana.

There are fist fights every single day at Marana.  At Marana Junior High this is a kid who needs a beatdown.

At Marana Junior High this is a kid who needs a beatdown.  Right there, in the twilight on the shoulder of the highway,

Right there, in the twilight on the shoulder of the highway,