Childhood memories are like polaroid photos in an old dusty box.

They don’t provide a cohesive autobiographical narrative, only brief flashes of insight into the murky past. You sort through the random images, shuffling them like playing cards, until one of them finally whispers to you, and a shard of memory is revealed, darkly, like a half-forgotten scent or song fragment.

It is from these small, disparate clues that you must fashion your origin story. But each time you take the box down from the shelf, there seem to be fewer snapshots inside.

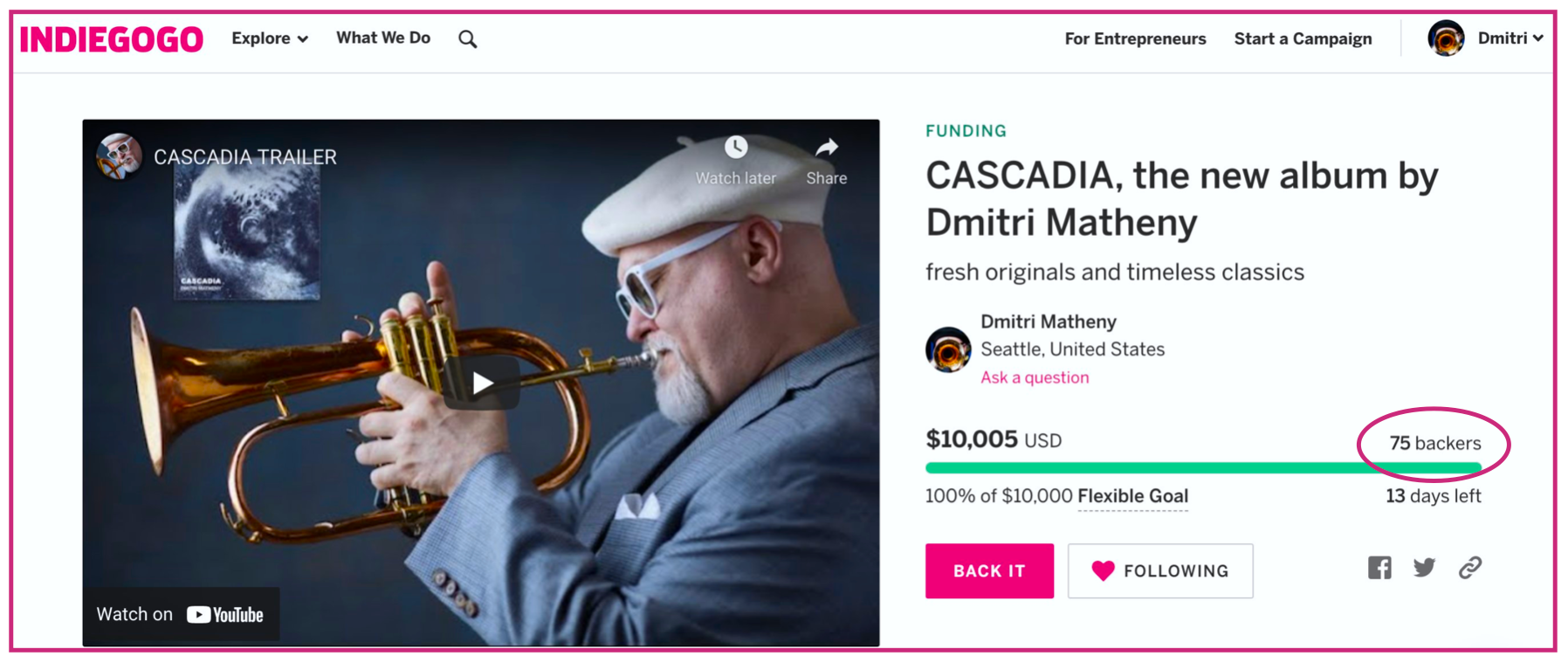

It’s the summer of 1978 in Columbus, Georgia. A U-Haul is parked in front of our little apartment at Warm Springs Court. Daddy Bill and I are loading our last few boxes into the back of the truck.

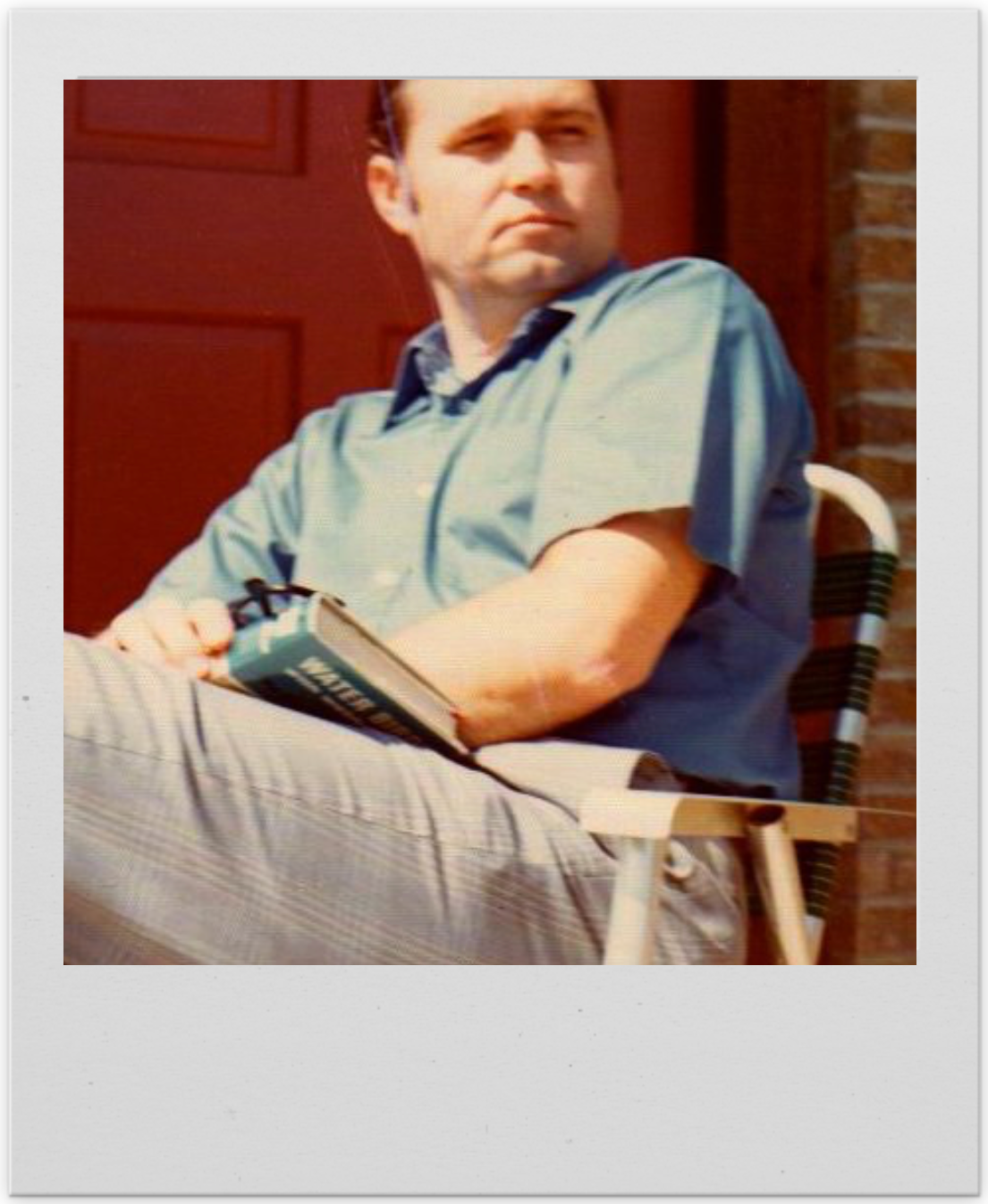

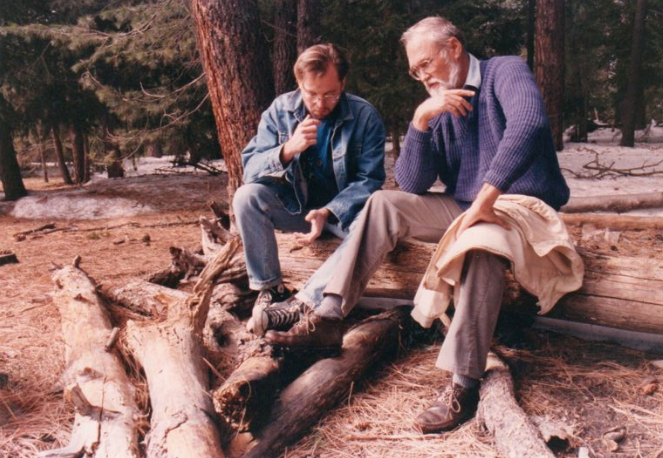

Daddy Bill Matheny | Summer 1978

Daddy Bill Matheny | Summer 1978

Warm Springs Court, Columbus GA

“You about ready to hit the road, Bub Man?” Daddy Bill asks. He’s been calling me “Bub Man” lately instead of Little Bub, and it feels right. I’m 12-and-a-half now, not a little kid anymore, and we’re about to begin a whole new life, far away from this place.

The past year was an emotional roller coaster. Up and down, love and loss. Dad finished his seventh year at Brookstone School on a high note, winning a prestigious teacher’s award from the city and having the yearbook dedicated in his honor. Then he abruptly resigned. Devastated by divorce, he slept for days at a time, rarely coming out of his room. “The doctor has me on tranquilizers,” he explained. When finally he emerged from the darkness of depression, other women came around, comforting him, playing mother to me, and we were happy for a time. But eventually they left, too.

When Dad’s last great love, Judy Mehaffey, moved to Nashville to pursue a songwriting career, her teenage son Jay came to live with us. Welcoming Jay into our home made sense. Our families were already intertwined. Jay’s mom and my dad, who still loved one another, were now prolific penpals. Jay’s older sister Kim, away at college, had been my babysitter and Dad’s star student at Brookstone. Kim and Jay’s father Lem (divorced from Judy, estranged from Jay) was the landlord of our little apartment complex.

Confused? Welcome to my world. The important thing is this: for one glorious summer I had a brother.

I was an only child who never especially wanted siblings. I cherished my solitude and was never bored. Daddy Bill and I were pals, and if I needed more companions there were always plenty of kids in the neighborhood. But Jay’s arrival in the summer of ’78 was right on time.

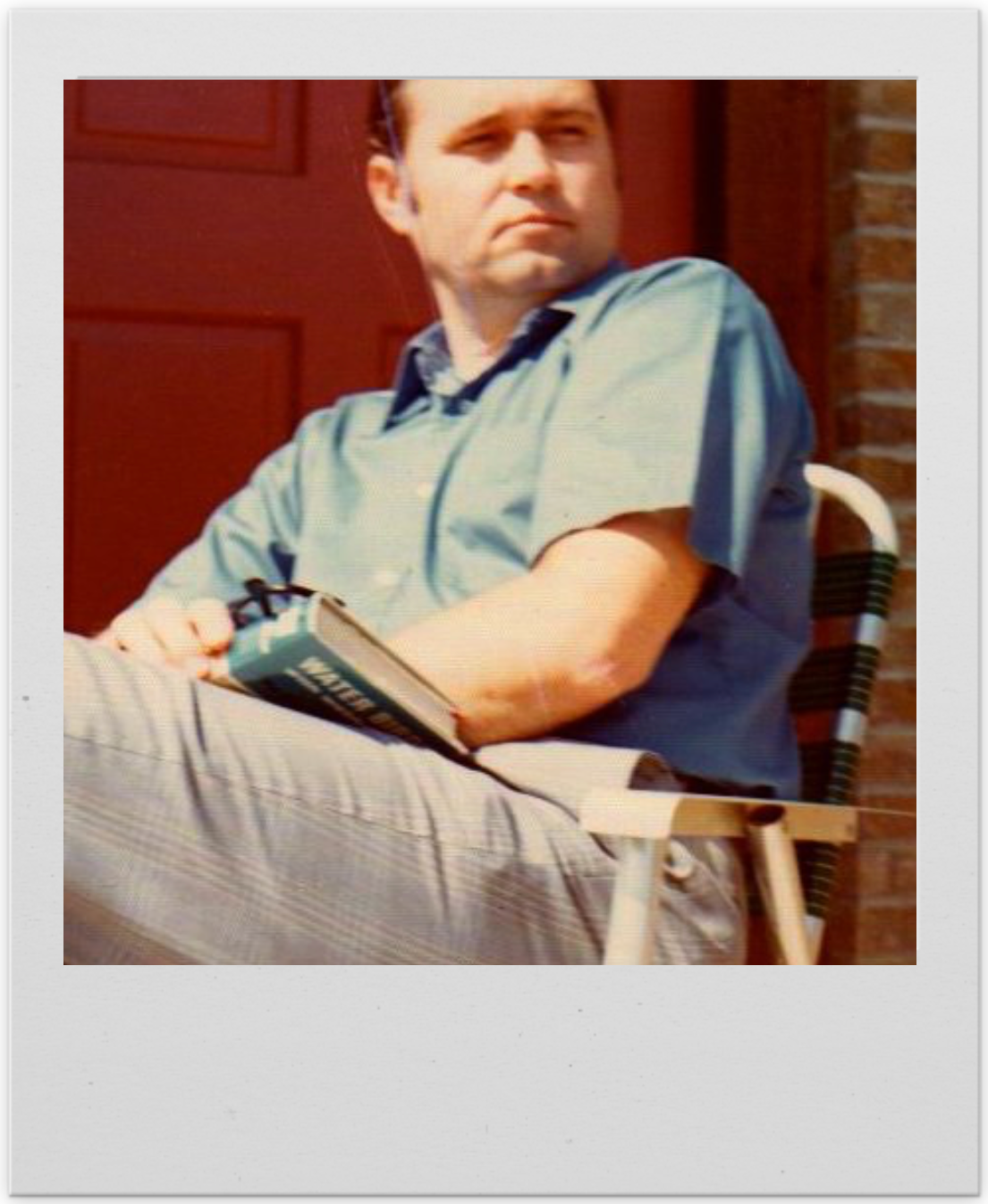

We lived in a small, two-bedroom apartment. Jay slept on our couch and made the living room his domain. As a tween on the precipice of puberty, I was utterly fascinated by this confident, lanky 17-year-old now living in our midst. It seemed like the most natural thing in the world, the way he immediately made himself at home, blasting Frampton Comes Alive on the stereo, watching Midnight Special on the tube, drinking Sprite, talking on the phone, holding court. I didn’t even try to play it cool. I thought Jay hung the moon, and he knew it.

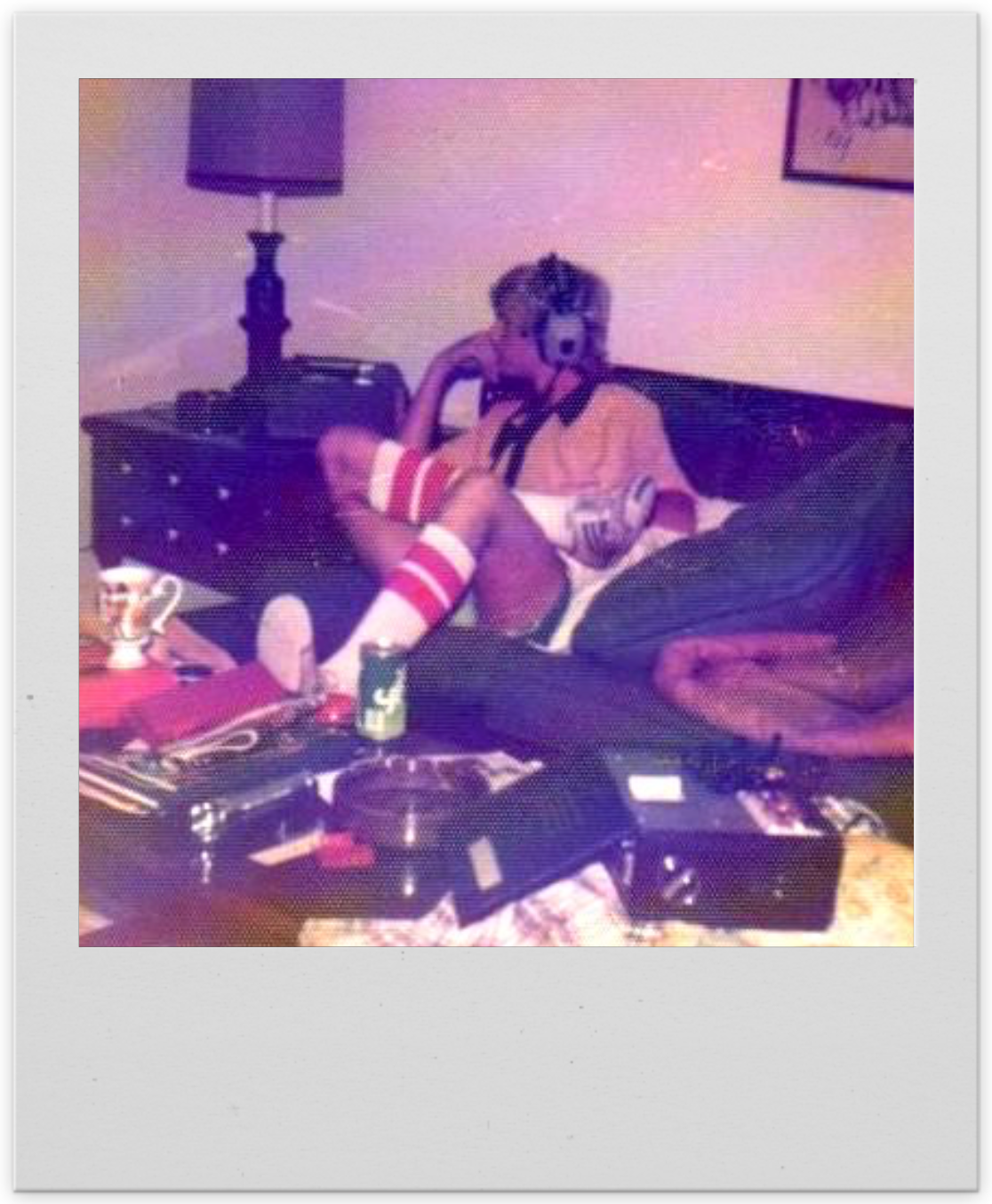

Jay Mehaffey | Summer 1978

Jay Mehaffey | Summer 1978

Warm Springs Court, Columbus GA

Dad knew it, too. Inviting Jay to move in may have sprung from a desire to help Judy, but it turned out to be the very best thing for all of us. Jay had a stabilizing influence in our home. His arrival prompted Dad to come out of his cave. Order was restored. We kept the pantry stocked, shared household chores, enjoyed regular meal times, and took road trips together.

Jay showed me how to assert my independence. Prior to Jay, I was Daddy Bill’s little sidekick, not so much a separate entity as an extension of his adult persona. I perceived Dad’s needs as my own; his moods became my moods. After Jay, I was my own man. There were three of us now, each with his own desires and responsibilities. We were a family.

But Jay was more to me than an ersatz older brother. He was like a cosmic life coach, sent by the universe to guide me through the emotional, hormonally turbulent life transition from boyhood to early adolescence. Our alliance felt all the more momentous because we knew it to be temporary. Summer’s end would mean our separation. Jay would stay in Columbus to finish high school, and I would move out west with Daddy Bill. Dad had accepted a new teaching position in Tucson, so that was where I would turn 13, begin junior high, and meet my destiny.

If Jay felt it was a drag to have a shadow that summer before his senior year, he certainly never showed it. He introduced me to his friends and let me tag along on their outings. He helped me find a job mowing lawns, taught me how to pop a wheelie on my bike, and hipped me to all kinds of music. At night I would make a pallet on the floor between the couch and coffee table, so we could continue talking into the wee hours. I’d stretch out flat, parallel to Jay on the couch above, and imagine that we were real brothers, sharing a room with bunk beds.

Our late night heart-to-hearts offered a crash course in what I should expect from life over the next few years. We talked about all the things I didn’t feel comfortable discussing with my father: cliques, crushes, flirting, fighting, parties, popularity, petty rivalry, peer pressure, the prom. I asked Jay all about the rituals of dating and how to talk to girls. He answered solemnly in great detail, stressing the importance of things like having plenty of money (chicks are expensive), when to give a girl your letterman jacket (only if you’re serious), and how to unhook a bra clasp (always use both hands). He spoke earnestly, as if he’d been tasked with a sacred mission of passing along his accumulated teen wisdom. I was riveted and hung on his every word.

Jay and I haven’t really stayed in touch since then, except to exchange Christmas cards once or twice, the way men do. But I sure hope he knows how important he was to me that summer, and how grateful I remain.

When the moving van showed up I was ready. Packing up was a breeze. After all, I’m the minimalist son of an anti-capitalist. We didn’t have that many possessions to begin with. Plus, we’d already moved several times before, so I knew the routine: put your stuff in boxes; say goodbye to all your friends.

Moving days are always bittersweet, but this one felt different. Inspired by everything I learned from Jay, I was committed to reinventing myself. I divided my belongings into two piles. One pile comprised only the essential things I’d need in my new life out west: clothes, books, trumpet, bike. We loaded them onto the truck. The other pile was all the “kid stuff” I would leave behind forever: comic books, action figures, toys.

Word got around quickly and the neighborhood kids descended like vultures. I sold everything I could and gave away the rest, pocketing a little over five hundred dollars.

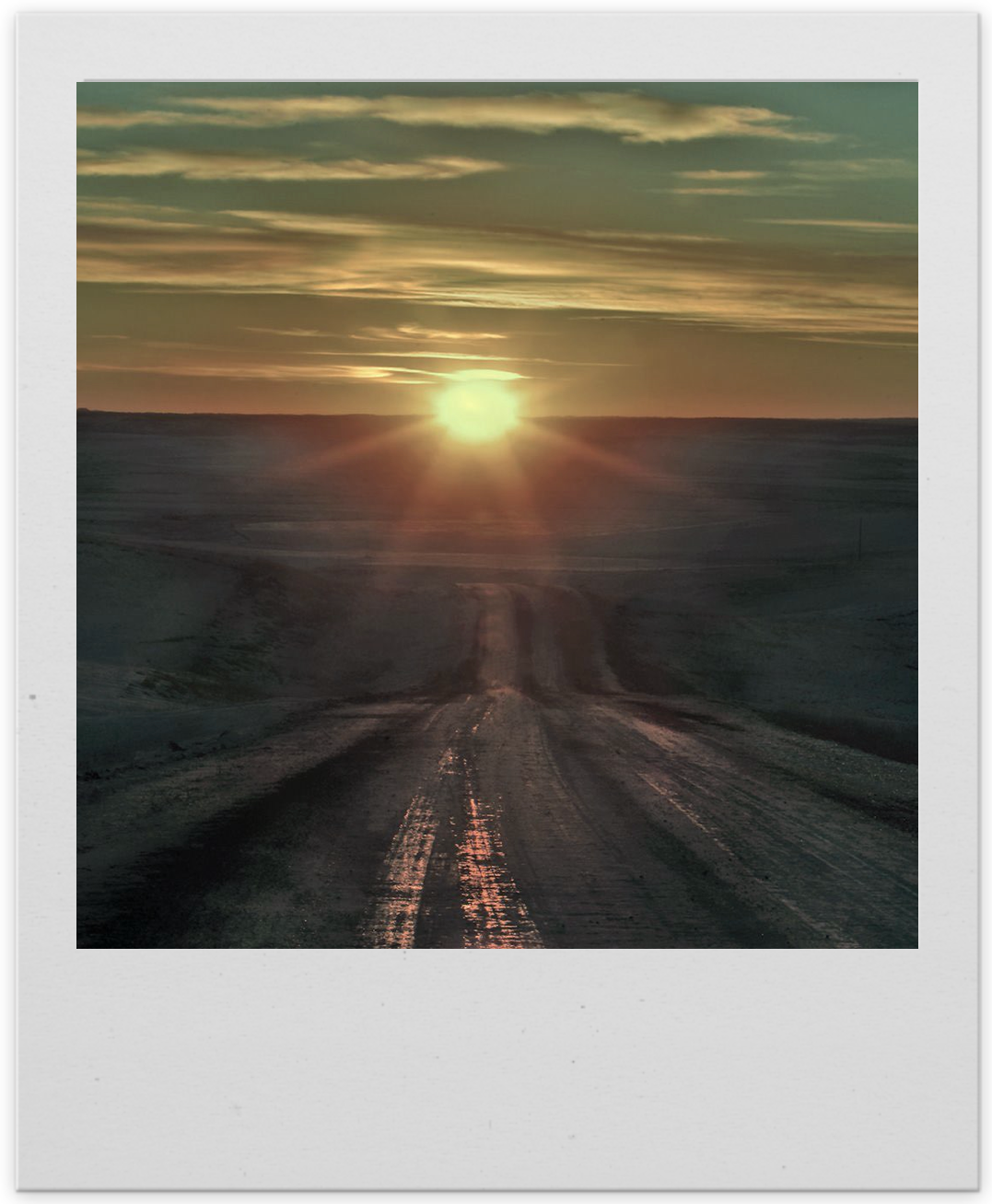

“You about ready to hit the road, Bub Man?” Daddy Bill asked. “You bet,” I replied, climbing into the cab.

I didn't look back as we headed west. To the future.

Next:

SNAPSHOTS | PART 2 — FIRST CONTACT

charted

charted  added

added  played

played  directed

directed

accompanied

accompanied  headlined

headlined  published

published  planted

planted  recorded

recorded  arranged

arranged  completed

completed

published 50 memoir blog posts

published 50 memoir blog posts

played 5 live stream shows

played 5 live stream shows

I used a platform called “StageIt” to produce my Quarantunes series of live-streaming solo shows

I used a platform called “StageIt” to produce my Quarantunes series of live-streaming solo shows The Immortal Bobby Hutcherson

The Immortal Bobby Hutcherson  Save Our Stages is an emergency relief fund for live event venues and promoters

Save Our Stages is an emergency relief fund for live event venues and promoters  Daddy Bill has always been in my corner

Daddy Bill has always been in my corner my three demons have tortured me for as long as I can remember

my three demons have tortured me for as long as I can remember  Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of keen awareness

Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of keen awareness  CBS Sunday Morning is usually a welcome comfort, but this episode made me anxious

CBS Sunday Morning is usually a welcome comfort, but this episode made me anxious xenophile hero Anthony Bourdain and friends showing us how its done

xenophile hero Anthony Bourdain and friends showing us how its done  grateful, but also anxious

grateful, but also anxious facing a world without him in it fills me with dread

facing a world without him in it fills me with dread