“Open your minds, my friends.

We all fear what we do not understand.”

—Robert Langdon

Charlie Higgins leads me by the arm into a space entirely unlike the rest of this mysterious fortress.

The dining room is sunny, warm, and elbow-to-elbow with convivial groups of men in business attire, eating, drinking, talking and laughing.

“This is us,” Charlie says as we approach a corner table where a couple of seated gentlemen rise to greet us. “Let me introduce you to two of the original hep cats, Walt Connor and Will Cooley. Gentlemen, this is Dmitri Matheny.” We all shake hands and sit down together.

At each place setting a single card embossed with the now familiar OC logo offers a simple selection of steak, seafood, sandwiches, and salads. I’m delighted. Since moving to San Francisco from Boston a few years ago I’ve enjoyed a steady diet of international and vegetarian fare. I’ve even learned to appreciate California cuisine with its requisite avocado, pine nuts and sun-dried tomatoes. But I was raised on American comfort food from cafeterias and diners. This is my kind of menu.

Nevertheless, I decide to order something I’ve never tried before, a Crab Louie Salad. Based on the name, I’m fairly certain that I will enjoy at least two thirds of it.

Over lunch, Charlie cheerfully embodies his role as table host, guiding the conversation so as to include everyone. In spite of our difference in age (I’m in my late 20s and they’re all in their 60s) we all get along swimmingly.

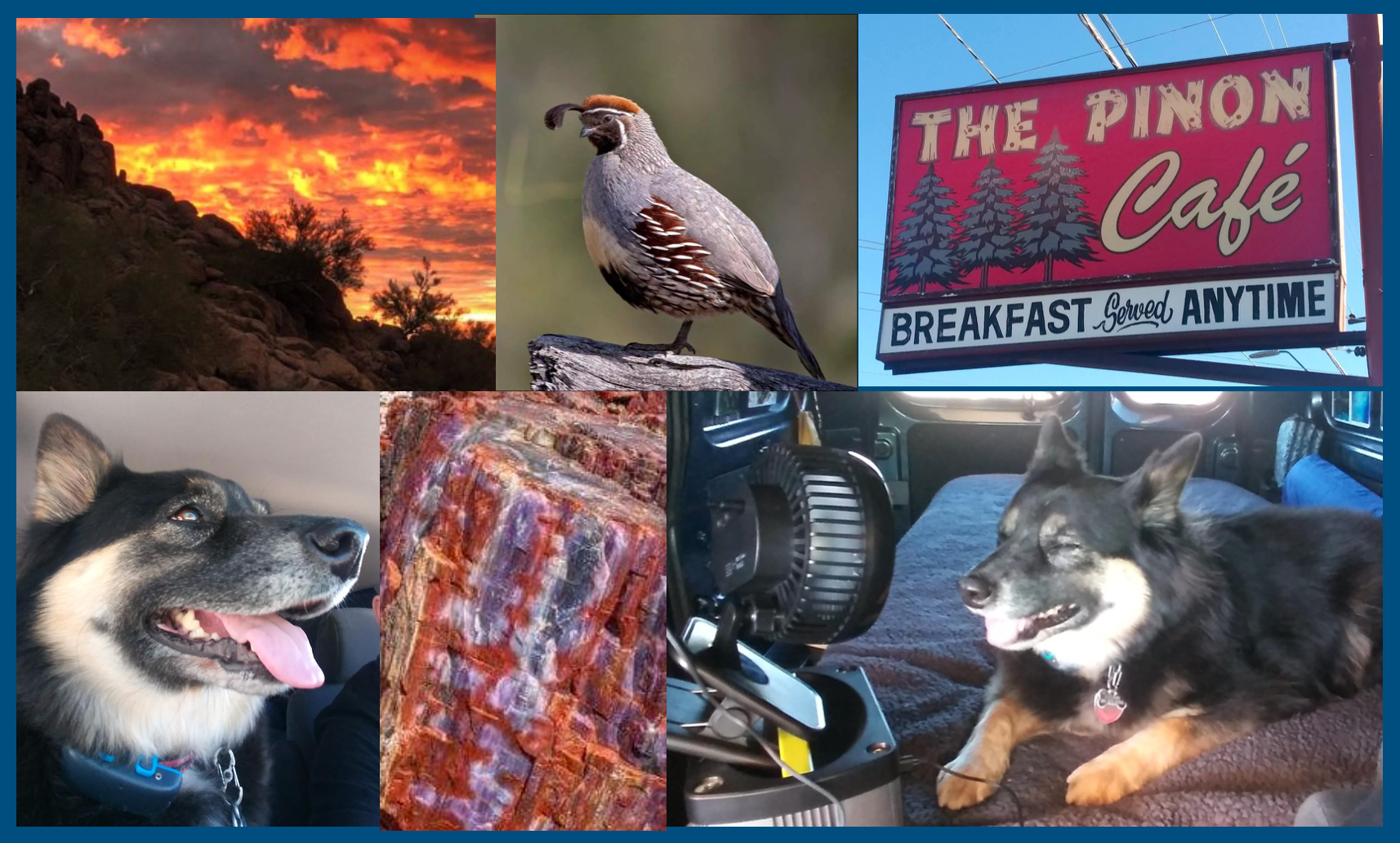

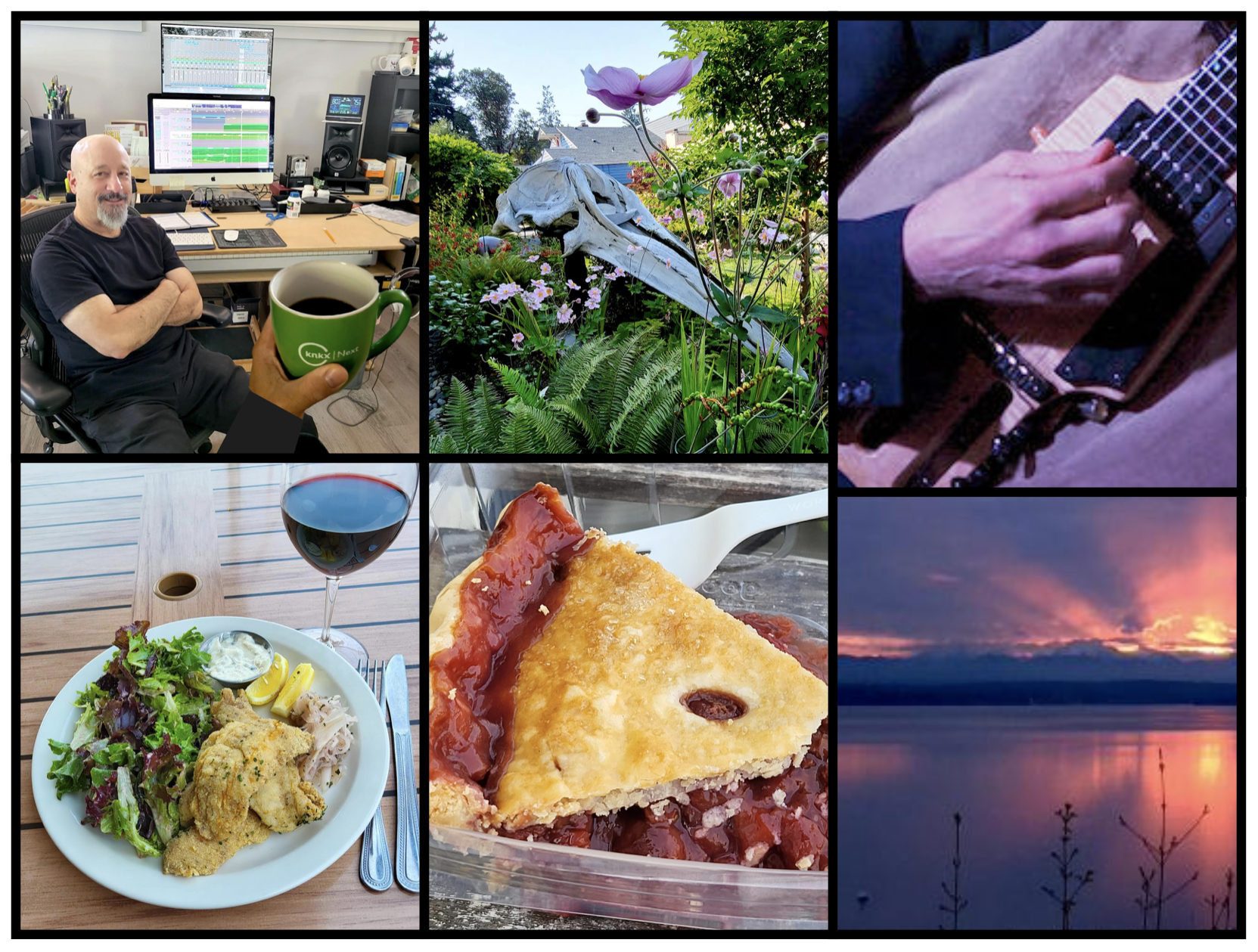

Curiously, no one discusses business. Charlie, the candy magnate, talks about his experience as a paratrooper in World War II. Will, a Southern California real estate developer, holds forth about Stan Getz and his involvement in the committee for jazz at Stanford University. Walt, an author and photographer (who may or may not also be heir to a large national department store fortune) speaks with authority about the forgotten history of jazz on the Barbary Coast. I mostly listen, fascinated by these wise old owls.

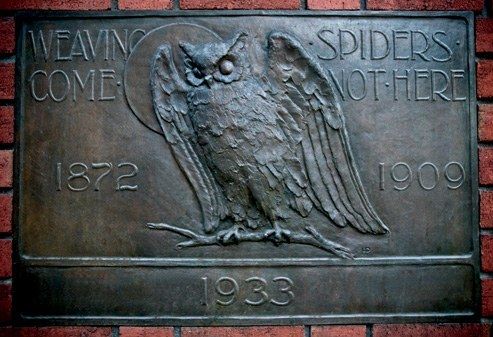

As coffee is served, Charlie casually turns the conversation to the unique history and ethos of the Owl Club. Unlike other quote-unquote secret societies and fraternal organizations, Charlie explains, we aren't centered around a particular industry, sport, or school, but a common interest in nature and the arts.

“Our membership roster includes not only prominent businessmen and CEOs,” Charlie says proudly, “but writers, journalists, military heroes, politicians, global leaders, and many well-known artists and musicians.”

I'm intrigued. “But no women?”

Charlie smiles. “You know, a hundred twenty years ago when this club was founded, men tended to stay in their unhappy marriages. They needed clubs like this as an escape. Of course these days, if you aren’t happily married, you get a divorce. That’s why so many of our happily married members are now requesting more events to which they can bring their spouses.”

Taking this as my cue, I pull the glossy jazz festival sponsorship brochure from my breast pocket and lay it on the table. I’m just about to begin my pitch when Charlie interrupts me, raising his hand and saying, “no-no-no, not here.” A red-vested waiter immediately approaches to ask that I “kindly put away the literature.”

“I’m sorry, I thought …” I stammer, befuddled.

“We can discuss all that later,” Charlie replies magnanimously.

At precisely this moment, as if responding to a silent alarm, everyone stands to say their goodbyes. I stand too, shaking hands with Will and Walt, who leave together.

Charlie places his arm around my shoulder and ushers me back through the grand foyer, past the empty bar with its mad jumble of framed art, to the dark alcove where I first entered the building. It looks somehow different to me now. Less off-putting. More cozy.

“What a pleasure,” I say. “Thanks for lunch.”

“Ah! I almost forgot!” Charlie replies, reaching into his pocket. He retrieves a small box, about 4 inches in diameter, wrapped in white paper. “This is for you.”

On my way back to the jazz office, I stop by the piano bar at Kuleto’s, my favorite Union Square watering hole. I find a seat by the fireplace and order a bourbon, neat, feeling not unlike a noir detective at the beginning of a perplexing new case.

I unwrap the mysterious gift box, genuinely curious what I will find inside.

Perhaps some chocolate truffles from Charlie's candy company? But no.

I place the heavy totem onto the table in front of me and study it.

No card, no explanation.

Just a tiny silver owl.

Next:

THE OWL CLUB PART 4 — SWEETS

charted

charted  added

added  played

played  directed

directed

accompanied

accompanied  headlined

headlined  published

published  planted

planted  recorded

recorded  arranged

arranged  completed

completed